by Fergal Martin, CTS General Secretary

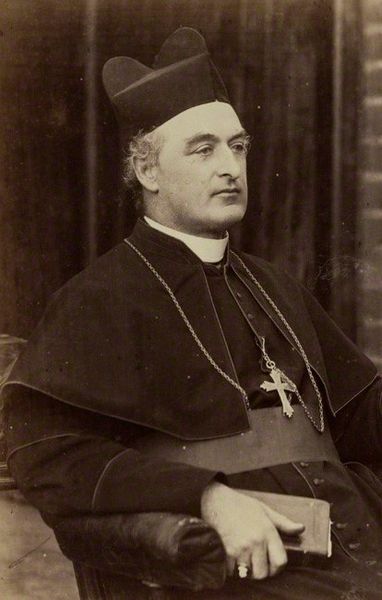

I’m staring at the photograph of a rather stiff-looking Victorian clergyman, tall and handsome. He has intelligent, tired eyes, yet there is determination in them, too. He was someone who longed to be a missionary all his life, and yet ended his long and energetic life as Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster. This is the person who founded the organisation I work for, the CTS, 150 years ago!

Herbert Vaughan grew up on the Welsh borders where he dreamt of being a missionary to Wales. From a wealthy, established Catholic family that had survived penal times, he was the eldest of thirteen siblings most of whom became religious or clergy. Tall, elegant, handsome, he was by all accounts a genuinely pious and holy man, spending two hours a day in prayer, and painfully aware of his many faults. He was simply put, a Christian man, who had learnt his faith from his mother. From an early age, he was overcome with the impulse to bring the good news of the gospel to those who were entitled to hear it.

Vaughan was never a parish priest or even a curate, but after training for the priesthood in Rome became vice-rector at the seminary at Ware. There, he investigated missionary and priestly training in many different contexts. He co-founded a missionary society of diocesan priests (the Oblates of St Charles), a revolutionary idea at the time. After travelling widely in Europe and America investigating missionary societies and seminaries, aged thirty-four he founded a new missionary order: the Mill Hill Missionaries. He had found his great mission for life.

At only 40 he was made Bishop of Salford, where he remained for twenty years, visiting all his parishes, and founding the Children’s Rescue Society, St Bede’s Commercial College for Catholic children and countless similar initiatives. Just a few years earlier, he had founded the Catholic Truth Society (to become known simply as ‘the CTS’), and it continues to this day as an active publishing charity. It began as a small pamphleteering outfit, inspired by what Vaughan had seen of the power of the Protestant printing press in America. Vaughan went directly to his audience: in parish churches up and down the country, he recruited ‘CTS boxtenders’, laypeople always at hand in the parish with a small, portable wooden box, opened up to display and sell half-penny booklets to educate and support the faithful and anyone else who dropped by.

It proved timely. Vaughan’s CTS produced thousands of inexpensive, accessible and popular tracts that were a source of knowledge, spiritual food, catechesis and novelty. Readership accelerated at unimaginable rates between the 1920s and 1940s: CTS’s benchmark was the best authors writing on the things that mattered. Readers were encouraged to leave their tracts, once read and digested, on the bus, on a park bench, on a train seat. The great movement’s army was then as it remains today: a combination of readers who could buy CTS booklet very cheaply and donors who gave generously to support the CTS mission to evangelise. In 2018 there are 7000 booklets in CTS’s archive. They all whisper the same forceful truth: God loves each one of us, he always has, deeply and without reserve, no matter who we are, nor what we have done.

Vaughan went on to buy The Tablet and the Dublin Review and was at the heart of Catholic communications for what they were in those days. For many years this involved writing and editing articles and proofs at his desk long into the night. He believed passionately that the truth itself has an overwhelming attraction, and must be communicated no matter how unpopular it might seem. People may reject it, or they may grapple with it, or accept it; but they certainly have the right to hear it, as it is.

Then came a request from the Pope that he become Archbishop of Westminster. Aged 60, he threw himself into Our Lord’s hands and gave it all his energy, despite recurring and increasing illness. He raised funds to build Westminster Cathedral, surprising everyone by the style and grandeur of the project. He wanted to put Catholicism back on the map, not just for the world to see, but to inspire and encourage his flock after centuries of being forced into the shadows. The first liturgy in the almost finished cathedral was his own requiem. He died at Mill Hill among his Missionary Order confreres on 19 June 1903, the feast of the Sacred Heart, after a long illness, aged seventy-one.

On CTS’s 150th birthday this year, we are grateful to Herbert Vaughan for his impulse to evangelise, his commitment to the truth, and for his life of love and service. A recent CTS research project among students at London University revealed that amid the mountains of meaningless information bombarding them every day, one key question persists: how can I live a meaningful and happy life, that works; what is the purpose of my existence? It is we who must provide a considered, logical, accessible and truthful answer.

Recently a young job-interview candidate, was asked why he wanted to work for CTS, said: ‘A couple of friends of mine in difficult situations, with real problems, were greatly helped by a CTS booklet … what you do helps people, brings them back to their bearings, gets to the truth of things. I’d like to be a part of that.’ As he spoke, his eyes reminded me of many others I have looked into in my journey here. Happy Birthday CTS.

For more information on the 150th anniversary of the Catholic Truth Society visit www.onefifties.org