by Fr Nicholas Schofield, Diocesan Archivist

The diocesan archive largely consists of precious documents relating to the history of the Catholic community in the London area. There are not many artefacts but two always intrigue me, and they now hang on the wall of my office: memorial plaques to two brothers killed six months apart in 1916. The plaques only came to light in 2015 when staff found them tucked away in a box of uncatalogued archives. They commemorate the deaths of Stephen and Daniel Ginn, but there were no clues as to where the plaques had come from or how they came to be in the archives. By pure chance, the mystery was solved a few weeks after their discovery when family historian Michael Kent happened to visit the diocesan archives in Kensington.

He was, it transpired, the great nephew of Stephen and Daniel Ginn. Michael was able to shed more light on the Ginn family, who were well-known in the Victoria area and owned a fruit and florist shop, ‘S. Ginn’, at 87 and 89 Wilton Road, Victoria. The shop was run by Stephen and Daniel’s mother, Mary Ginn, who was better known as ‘Polly Ryan’. Polly was born in Old Pye Street, once the site of one of London’s most notorious slums. Situated only a stone’s throw from Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament, Old Pye Street achieved lasting notoriety in the 19th century when Charles Dickens dubbed it ‘the Devil’s Acre’. Although the Ginn family certainly knew poverty and deprivation, as did many growing up there, Polly and her children were determined to improve their lot. Polly started her career with a flower barrow at Pimlico Road and then Warwick Street. As well as opening a shop, Polly sold flowers outside the Army and Navy store and went early each morning to buy fresh stock at Covent Garden. She clearly appreciated the finer things in life, and developed a keen interest in antiques. She often visited auction houses and ‘as she arrived,’ we read in a local paper, ‘they used to say “Here comes the Little Duchess of Pimlico”’.

By the time she died in 1935, Polly Ryan was described as ‘almost an institution in Covent Garden’. However, life was not easy for her and the inscription ‘No Mother has suffered so much/No other had greater love’ was included on her tombstone. She bore 15 children, of whom four died in infancy, including her youngest child, Francis Xavier, who was less than a week old when he died in 1903. Then on 20 March 1914 her husband, Samuel, passed away at the early age of 57.

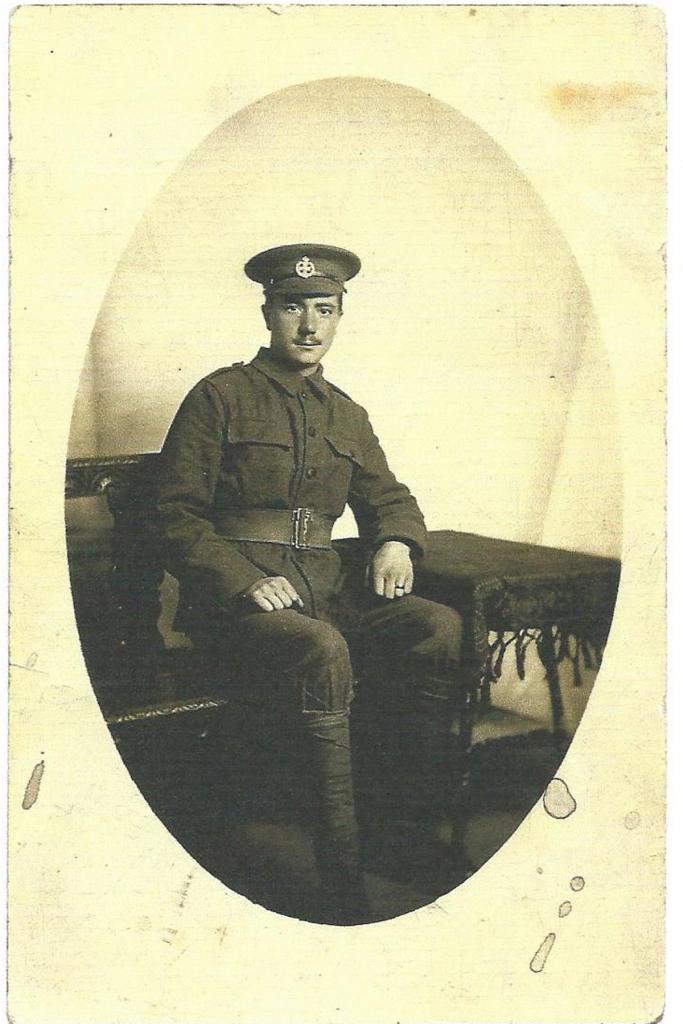

Further tragedy ensued during the First World War. Polly’s son, Stephen, had joined the 2/Prince of Wales’ Leinster Regiment and rose up through the ranks to become a sergeant. Catholics in England were often recruited into Irish regiments and in Stand To!, the memoirs of Colonel Francis Clere Hitchcock, MC, Stephen Ginn was described as ‘a fine soldier’ and ‘the only Cockney in the Battalion’. Stephen was killed in action on Sunday 5 March 1916 at Ypres. Fr Denis Doyle, Chaplain to the battalion, wrote to his mother: 'Your son Stephen was wounded early this morning and died about two hours afterwards, a beautiful and holy death. He was a good fellow and a splendid Catholic. As a sergeant he was well liked by his men. He was shot through both lungs with a rifle bullet. When I went to his side he said “Father your blessing. I am dying.” I put my Crucifix before his eyes and he said “Oh Father isn’t it beautiful, and I am going to him, my God. Tell my mother and friends.” He muttered more about all at home, which I did not quite hear. I gave him all the Last Sacraments of the Church. Again when the pain got great and he could not endure it I showed him my Crucifix and he said “Oh isn’t it beautiful, not so much pain as his.” I held up his head and gave him a little water to quench his thirst. He then silently sank to rest, his last words were “Tell them I died like a man.”

'This must bring you the greatest comfort it is possible to have on earth – to know that you had a son who could die like that and who I am sure is happy in heaven today. If you need more comfort then unite yourself with the Blessed Virgin, at the foot of the Cross, who saw her Son offered in sacrifice. I have said Mass this morning for the repose of Stephen’s soul, and shall lay him to rest tonight in a little graveyard nearby. I shall see that a Cross is placed over this hero. I took his watch and a few things which I shall send to you.' (5 March 1916)

This ‘little graveyard’ Fr Doyle wrote of grew to become the Menin Road South Military Cemetery with some 1,657 Commonwealth war burials. Fr Doyle himself was to die less than six months later during the Battle of the Somme, hit by a shell burst in the early hours of 19 August while bringing tea to men in the trenches. Severely wounded, he was taken back behind the lines where he eventually died that evening.

Less is known about Stephen’s brother, Daniel Ginn, who was a Lance Corporal in the 9th Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own). His battalion had been involved in the fighting at Delville Wood on the Somme and, according to Army records, Daniel was wounded on 27 August 1916, finally succumbing to his injuries at Rouen on 15 September, aged 26 years old. He was buried in St Sever Cemetery.

Thanks to Michael Kent, we now know that it was Daniel and Stephen’s younger sister Florence who commissioned brass plaques to commemorate her brothers at the church of St Peter and St Edward in Palace Street, where the family worshipped and where most of the children were baptised. Florence, with the help of her sisters, Ivy and Kathleen, carried on running their mother’s flower shop in Wilton Road until Florence retired in the 1960s. The church in Palace Street closed in 1975 and it was probably at this time that the plaques were transferred to the archives where they lay undisturbed and forgotten for 40 years. Now the courage of these two Cockney brothers, born and brought up within the shadow of the cathedral and representative of that lost generation, is honoured and commemorated once more by their family and by the diocesan archives.