This article first appeared in the May 2016 edition of the Westminster Record and is written by Andrew Nicoll.

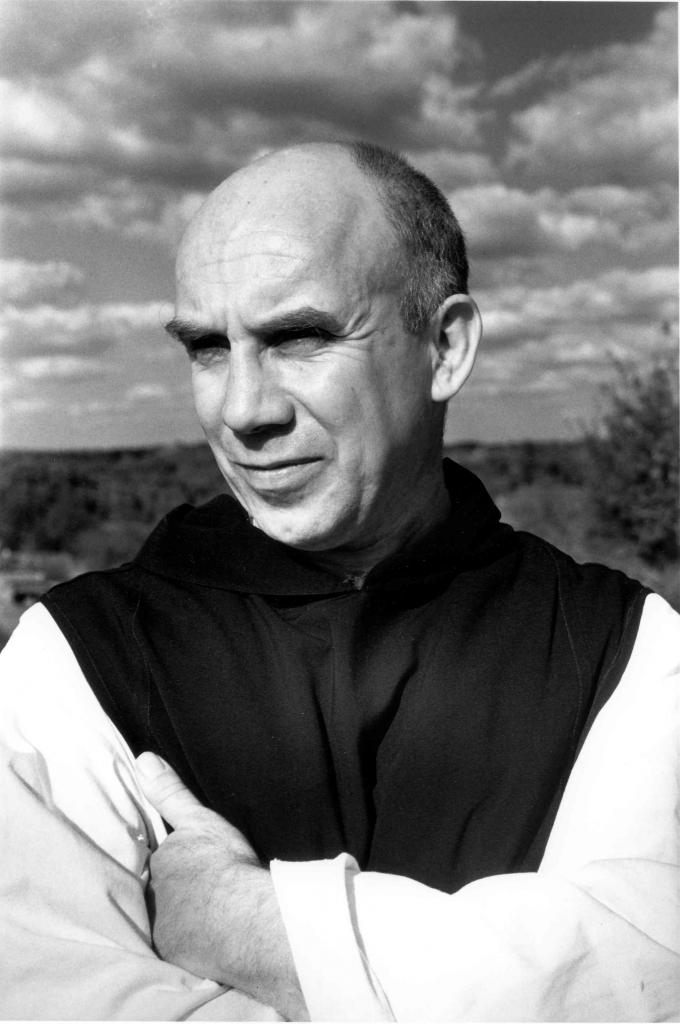

Both during his lifetime and since, Thomas Merton (1915-68) has always evoked a mixed response. Merton was educated at Oakham School, Clare College, Cambridge, and Columbia University whence, after a brief period as a university teacher, he entered the Trappist monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemani, Kentucky, in 1941, having been received into the Church three years previously. It was here he first became famous as a spiritual writer with the publication of his autobiographical work, The Seven Storey Mountain.

Merton prefigures the universal call to holiness of the Second Vatican Council. Contemplation was central to Merton, and he deserves careful re-reading during this Jubilee of Mercy. Contemplation is the ‘experiential grasp of reality as subjective.’ Furthermore, ‘Hell can be described as a perpetual alienation from our true being, our true self, which is in God.’ Surely, this is partly what the sacrament of Reconciliation is about: being true to ourselves through living the kind of life God wants for us. And ‘because our sins concern the whole Body of Christ they must be confessed to another and forgiven by another in order for our reconciliation to Christ in his Church to be complete’ says Merton. Perhaps as a guard against the trends of his own time (and ours), Merton made clear what contemplation is not: it is not a trance, nor a gift of prophecy, and often does not lead to definite knowledge of God, at least not initially. There is no ‘psychology’ of contemplation.

Extensive Correspondence

Merton died near Bangkok in 1968 whilst attending an interfaith conference on spirituality, and his body was flown back to United States by an aircraft on its way back from Vietnam. In addition to biographical and autobiographical works, Merton wrote poetry and spiritual books. His diaries extend to several volumes and his letters number in the thousands. Merton corresponded with Popes, writers and thinkers, and spiritual figures from other denominations and different religions, being one of the first in the Church to do so seriously. He was a noted peace and civil rights activist during the troubled times of the 1960s in the USA.

Deep Spirituality

It is regrettable that many of the impressions people have of Merton seem to be based on his activism and later writings, some of whose themes are vulnerable to politicization. This is exacerbated by the general shift to the political right seen in both the UK and the USA in the decades since the 1980s, especially with respect to defence. Perhaps, too, the deep spirituality which underpinned Merton’s views does not always accompany similar opinion today. Finally, the ecumenical movement which blossomed in the 1980s was sometimes misunderstood as ‘let’s make everyone the same’ rather than developing a genuine understanding of the traditions of different faith groups.

In my view, Merton has much to commend him as long as one considers the whole man. For many years, Merton lived under the authority of Abbot James Fox who once described Merton as his most obedient monk. Fr Louis (his name in religion) said Mass and read the breviary in Latin even post-Vatican II, cherishing a deep respect for the Church as the mystical body of Christ. ‘It is in the Mass that we are united to Christ from whom all the graces of prayer and contemplation flow,’ he wrote. In a diary entry from 1967, Merton describes a Sunday Mass in the monastery following the liturgical changes: ‘At the end we all recessed singing “The Church’s One Foundation” which reminded me of dreary evening chapel at Oakham 35 years ago. Renewal? For me that’s a return to a really dead past. Victorian England.’ Above all, he was a mystic, a ‘monk of mercy.’ Mercy can heal the body and spirit, and all of society and history, being ‘the only force which truly heals and saves,’ he says. Mercy can be found in the Church, a ‘community of pardon, [and] therefore a community of penitents … not a community of judgment.’ How appropriate for the Year of Mercy!

Celebrating Merton’s Centenary

Among the organisations around the world dedicated to Merton and his works is the American-based International Thomas Merton Society which held its meeting commemorating the centenary of Merton’s birth at Bellarmine University (Kentucky) in 2015; the former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Rowan Williams was a keynote speaker. The Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Ireland held its centenary meeting in April at Merton’s old school, Oakham School, under the title Life is on our side. There are approximately 195 books written in English on Merton with more on the way, and renewed interest in Merton has led to, it is thought, six or so students taking up PhDs in the UK on aspects of his work, the most ever. The Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University usually receives six to 12 doctoral or masters theses each year.

‘Above all a man of prayer’

In his speech to the US Congress in 2015, Pope Francis praised Thomas Merton as ‘above all a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church.’ The year 2015 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council and, half a century on, there are still those lamenting Merton and ‘the spirit of the Vatican Council.’ I believe this, in part, stems from separating the political Merton from the spiritual Merton, the Merton of contemplation and mercy, universal qualities which Merton proudly holds up as a mirror in which we can all gaze upon ourselves. Consequently, he also has much to offer ecumenically: ecumenical in the sense of whole Church. Merton once said ‘Mercy within mercy within mercy’. We need more mercy in the world, more authentic contemplation in our lives, and a greater sense of the presence of Christ in the sacrifice of the Mass. Now is the time to appreciate Thomas Merton.

Dr Andrew Nicoll FRSB FRSA is a schoolmaster of Oakham School.

Photograph of Thomas Merton by Sibylle Akers. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University.