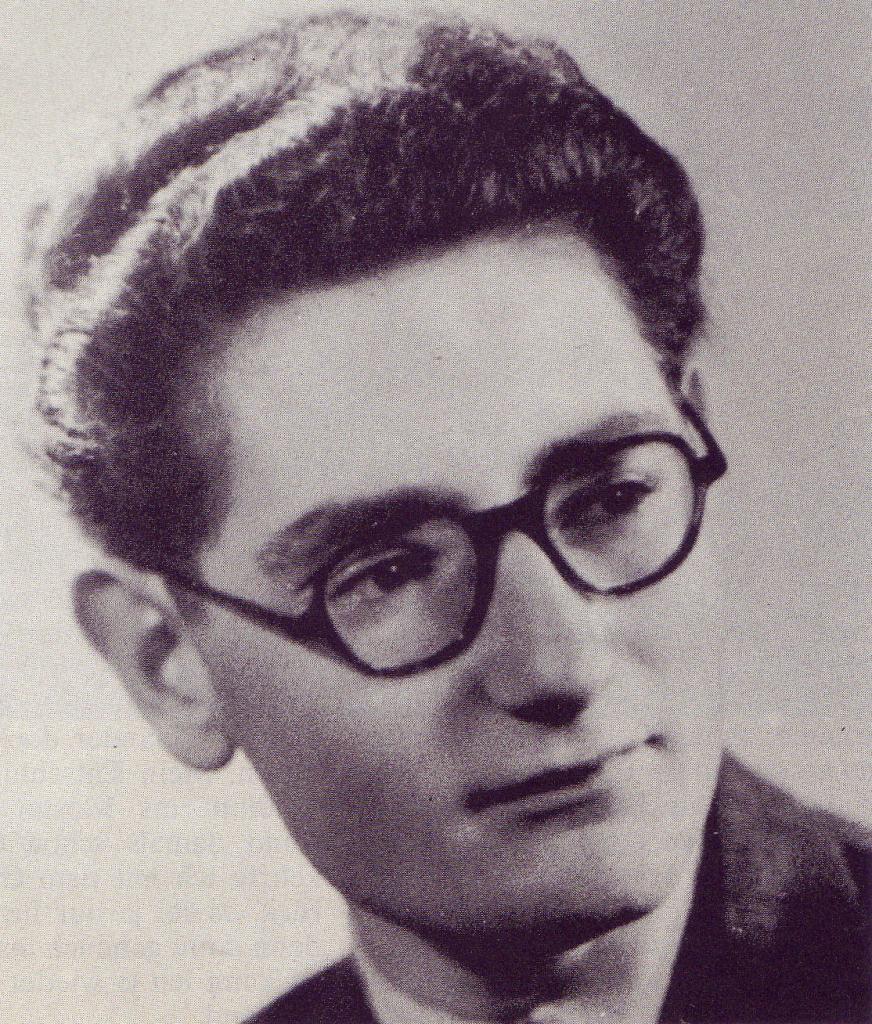

Fr Francis Wahle turned 90 this year, and although he has been retired for a good number of years, he remains in active service. In this interview, he shares the story of his remarkable life.

Around the time of his ninth birthday, an event happened which dramatically altered his future. At the time he lived in Austria with his parents and sister; but over the border, an authoritarian regime was on the rise with an intense anti-Semitic bent. Although not Jewish himself, Fr Francis had Jewish grandparents, and so according to the Nuremberg laws of 1935, he was considered racially Jewish. But it was Kristallnacht, ‘the Night of Broken Glass’; a night in November 1938 which resulted in the destruction of over 7,000 Jewish businesses, that precipitated the reaction to move him and his sister somewhere far from Hitler’s Lebensraum. Before then, Fr Francis admits, ‘Nobody knew it was going to be slaughter. They thought it was going to be slave camps perhaps, confiscation of property, things like that. But Kristallnacht made it so clear that whatever it was, it was going to be really nasty’.

This was of course the Holocaust and the deaths of over 6 million Jewish people. Thankfully, due to what is now known as the ‘Kindertransport’, Fr Francis, his sister and many other children were able to escape what was coming. ‘I think the first one actually was from Germany as a result of the parliamentary discussions with Eleanor Rathbone and others in this country, who finally boxed through the quota of 10,000 unaccompanied children. And I came under that. Along with my younger sister, a whole lot of children, we travelled by train with some soldiers or Gestapo in the carriages with us. It was rather grim, as you can imagine.’

The terms of the Treaty of Versailles following the First World War had been punitive for both Austria and Germany. As Fr Francis explains, it ‘dismembered Austria, stopped it from really flourishing, and so a lot of people were hankering to go find a big brother or a big sister, namely Germany, to join together. So there was a great wave for amalgamation with Germany.’

It was in this climate that Fr Francis’ parents read the signs of change and arranged for their children to escape. ‘I don’t know at what stage my parents were aware of the possibility [of the Kindertransport], but until that time, we were busy learning Italian because our family in Italy was going to be the people to send us to, but we couldn’t get all the papers, so when Kristallnacht came, my parents just switched over. My mother had connections among the Soroptimists and other clubs, where she found out about this. And so for them it was a way of at least getting us out.’

When asked if he was aware that this was an escape, Fr Francis said that to him it was more of an adventure. But his sister ‘picked it up very quickly that this was a very sad occasion because she could see my parents were very anxious. And from the parents’ point of view, it was awful. Can you imagine, sending your children away into the unknown? You’re sending them to a country which speaks a different language, which has different customs, different food, different dress, a different way of travelling on the roads.’

As for his parents who were left behind, ‘they were able to slip away and go into hiding for three years, and survived. With two children, none of us would have. And if we had been taken, we would have been sent to Auschwitz and we would have been dead by the end of that year.’

He goes on to reflect, ‘so I’m 90 now. I’ve had 77 extra years; I know that because if they hadn’t sent us away I would have been dead at the end of 1942, like Edith Stein and Anne Frank who perished around this time. It was the start of the extermination camps.’

When they arrived in Britain, the situation was confusing to say the least. ‘They had told my parents that a man from Norwich was going to be fetching me from Liverpool Street Station. He never turned up!’ On the other hand, his sister in fact went ‘to some nuns in the East End of London, where she was most unhappy because they had no idea of how to treat her. She was a very spoilt girl, we were all spoilt children, and suddenly she was being told, here’s your food. You don’t want to eat it? Alright, you don’t get any more.’

Instead, Fr Francis ended up at a house loaned to the Catholic Committee of Refugees in Crawley Down along with several other refugee children. Although separated, the siblings occasionally saw each other, with his sister eventually moving back to Vienna after the war, joining the nuns who had taken her in, and becoming very well known for her work in improving Catholic and Jewish relations, as well as being the first religious to teach in a council-school under the Soviet occupation of Vienna.

Fr Francis himself was sent to Stonyhurst, eventually finishing in 1947, by which time his parents had resurfaced out of hiding and helped organise a stipend for him to study Economics at University College London. This was followed by ‘four years’ study to become a chartered accountant, then five years in John Lewis and then the Lord got me. So at the ripe old age of 30, I went down to Rome to do my studies at the English College.’

In the end, Fr Francis attributes his call to a natural progression. Already active as a layman, he knew a number of priests. ‘One of them once said to me, “Why aren’t you a priest?” I’d never been asked the question that way round.’ But also, he says, ‘I think, behind it all is probably a sense of gratitude. Without God’s doing, all four members of our family would have

been dead.’

This gradual call became firmer upon entering seminary. ‘The first thing they did in those days was to throw you into a retreat. And at the end of that retreat I was certain. Now, many of the other lads took years to discern. Mind you I was much older. Of the 12 in my year, I think four were under 18, and I was 30.’

In fact, his time at Rome coincided with the Second Vatican Council, and so he was right in the midst of the discussion and debate. ‘You see, we were lectured by the Jesuits at the Gregorian University, who were periti (theological advisers to the Council), so we were getting the stuff which was going into the council documents from the people who actually put it there. We had the whole of the English hierarchy living in the English College so we knew them personally.’

Moving back to England was an experience for him. He came back a bit of a stranger as most priests then were trained at St Edmunds. He remarked, ‘funerals were a great occasion, especially a priest’s funeral where you could meet a few more!’

His first placement was at Westminster Cathedral, a place he describes as ‘more or less like an Oxford club’, with a group of chaplains living together. After eight years at the cathedral, he moved to East Acton and served as Catholic chaplain for Hammersmith Hospital. This was followed by five years at Allen hall, 11 years at Enfield, 12 years at Queensway, ‘and now 15 years retired.’ Although as he went on to specify, not so much retired as simply ‘not in charge of anything’. He continues to say regular Masses in a number of parishes and is a familiar face to many around the diocese.

Among all the stories of parish and chaplaincy ministry, one story which stands out is from his time as chaplain at the old Westminster Hospital was when he gave out the cards his predecessor left, with hospital notices on one side, and a verse from scripture on the other. Now, although his predecessor never went into the maternity ward, Fr Francis did. ‘I went into the maternity ward and after about a month one of the nurses said, “Father, would you mind not giving these cards to those who’ve had caesareans?” “Well, sure, but why”, I asked. She said, “they laugh so much they burst their stitches”. So I looked at the card and it said, “Come to me all you who labour under a heavy burden!” (Matthew 11.28)’

Of all the things which are remarkable about Fr Francis, it is this sense of humour and self-awareness. When we asked about advice for priests nowadays, he said, ‘It’s no use, you simply can’t do what you did then, you know.’ But he encourages creativity and taking risks. As he said ‘as a general principle, nothing is ever wasted. You may think it is, but it isn’t’.

When asked about what he sees as the future of the Church, he is candid, saying, ‘I can give you a sort of nice, optimistic picture but I suspect the Church has to suffer first and lose a lot of what it has. We’re too comfortable and we’re not poor enough … I think we’ve got to go down first before we’ll go up.’ But, as he remarks, ‘well, we’ve got a good precedent. Our good Lord first went down to the grave.’