by Fr Nicholas Schofield

Up until recently England and Wales could claim one of the largest groups of martyrs officially recognised by the Church, at least since ancient times. This has been recently challenged by the martyrs of the 20th century – those who suffered in Mexico, Spain, Nazi Germany and the Soviet bloc. In many ways these modern persecutions were even more horrific and intense than those of Elizabethan and Stuart England. But martyrdom is not something we can measure quantitatively. Every single martyrdom is a miracle of grace; by definition, every single martyr is a witness to the Good News.

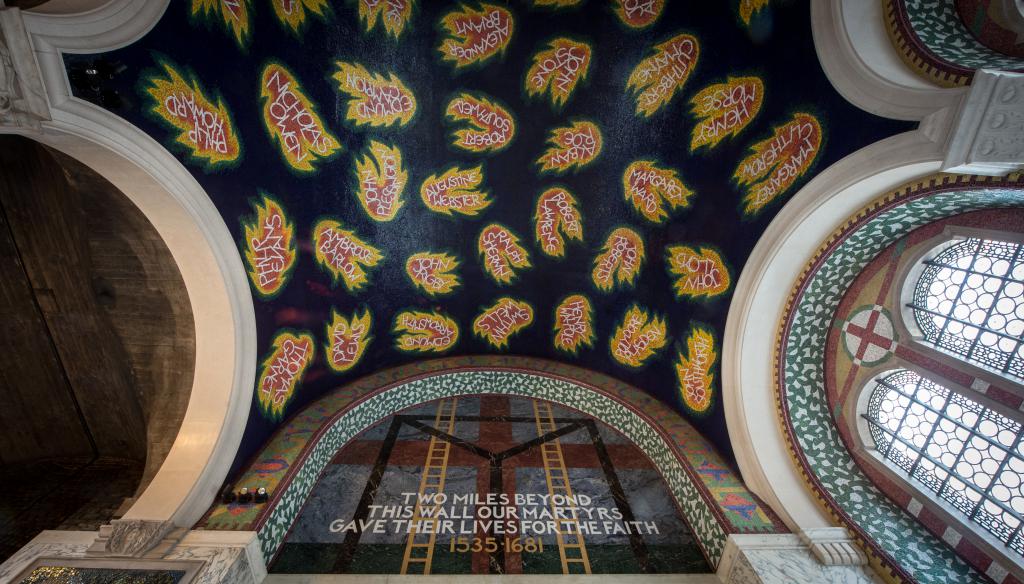

Suffering for the Faith between 1535 and 1680, most of the English Martyrs were priests, but they also included many laymen and women. One thinks of those brave female martyrs, Ss Anne Line, Margaret Clitherow and Margaret Ward; women were heavily involved in the life of the Catholic community but the authorities were reluctant to sentence them to death, which is why there are only three of them recognised as martyrs. One also remembers the likes of Blessed Roger Wrenno, a weaver from Chorley (Lancashire), accused of harbouring a priest at his house in 1616. He was hanged but the rope broke on the first attempt and, on regaining consciousness, was offered his life if he recanted. This he refused.

2018 sees the 450th anniversary of the foundation of the English College, Douai, in what is now northern France. This College acted as a school, seminary and college of further education and made an essential contribution to the survival of English Catholicism. A new generation of ‘missionary disciples’ was produced for the dangerous English Mission, 158 of whom were martyred simply for being faithful priests. The first of their number to suffer was St Cuthbert Mayne in 1577. Many of the Douai Martyrs, however, remain relatively unknown.

Blessed George Haydock, for example, returned to England but after only a few weeks in London (where he lived discreetly near St Paul’s churchyard) he was betrayed and arrested. Indeed, his first Mass on English soil was celebrated in prison. For 15 months he endured solitary confinement in the Tower of London and was involved in frequent disputations with Protestant ministers. Accused of conspiring against the Queen in Rheims (even though he was not in that French town at the time), the priest was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on 12 February 1584, aged 27.

Blessed Nicholas Postgate, on the other hand, was aged 80 at the time of his martyrdom. He lived for many years in a simple thatched cottage near Ugthorpe in Yorkshire and was known as ‘the Good Samaritan of the Moors’. He posed as a gardener and travelled long distances caring for local Catholics. It is said that he planted wild daffodils to commemorate his sacramental ministry and these can still be seen in the Esk Valley. He was finally arrested while celebrating a baptism and martyred on 7 August 1679, one of the last of the English Martyrs

Many moving stories were handed down about the martyrs’ final days. Blessed John Sandys (1586) was allowed to celebrate Mass the morning of his execution and delivered a moving exhortation to the congregation (though his execution was bungled by the inexperienced executioner); Blessed Alexander Crowe (1586) freshly shaved a tonsure on his head to show his pride in the priesthood on the day of his death; Blessed Richard Simpson (1588) embraced the ladder and kissed its steps as he was led to the gallows; Blessed Joseph Lambton (1592) encouraged his fellow victims with the words, ‘Let us be merry, for tomorrow I hope we shall have a heavenly breakfast.’

The English and Welsh Martyrs are truly representative. They came from a variety of backgrounds, ages and professions. Every part of the country (and, indeed, diocese) has at least one link with a martyr. As Cardinal Hume once said, ‘they all lived in our land, walked the same fields and lanes, lived under the same skies and, to their contemporaries, appeared to be perfectly ordinary neighbours. They show that sanctity is within the grasp of any of us. What was special about them was the way in which they were dedicated to Christ, steadfast in prayer and generous in the love and service they offered to their families, neighbours and friends. The strength of their commitment to faith was stronger than all opposition, even death itself. They are an inspiration to Christians of every church in the daily following of Jesus Christ.’