by Mgr Roderick Strange

If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me’ (Mark 8:34). Jesus’ words are familiar and stark. The path of holiness is laid out before us all too clearly. We are invited to embrace the paschal mystery. And it may overwhelm us. Our own share in the Lord’s passion may not be dramatic, but we can experience it in a number of ways. There may be various dyings and risings that we have to endure, more than one, ill-health, disability, the collapse of cherished plans, failed relationships, and, often most keenly, the death of those who are dearest to us. Those experiences make life seem more like a living death. We feel annihilated. And yet, if we refuse to be smothered by these disasters, but press on, keeping our hearts open somehow, we’re not sure how, but open somehow to love and the light, we find the situation changes. We move on from what seemed annihilation to a new, a risen, life. Discipleship, the call to holiness, is a matter of following that path, embracing the paschal mystery as it unfolds for us.

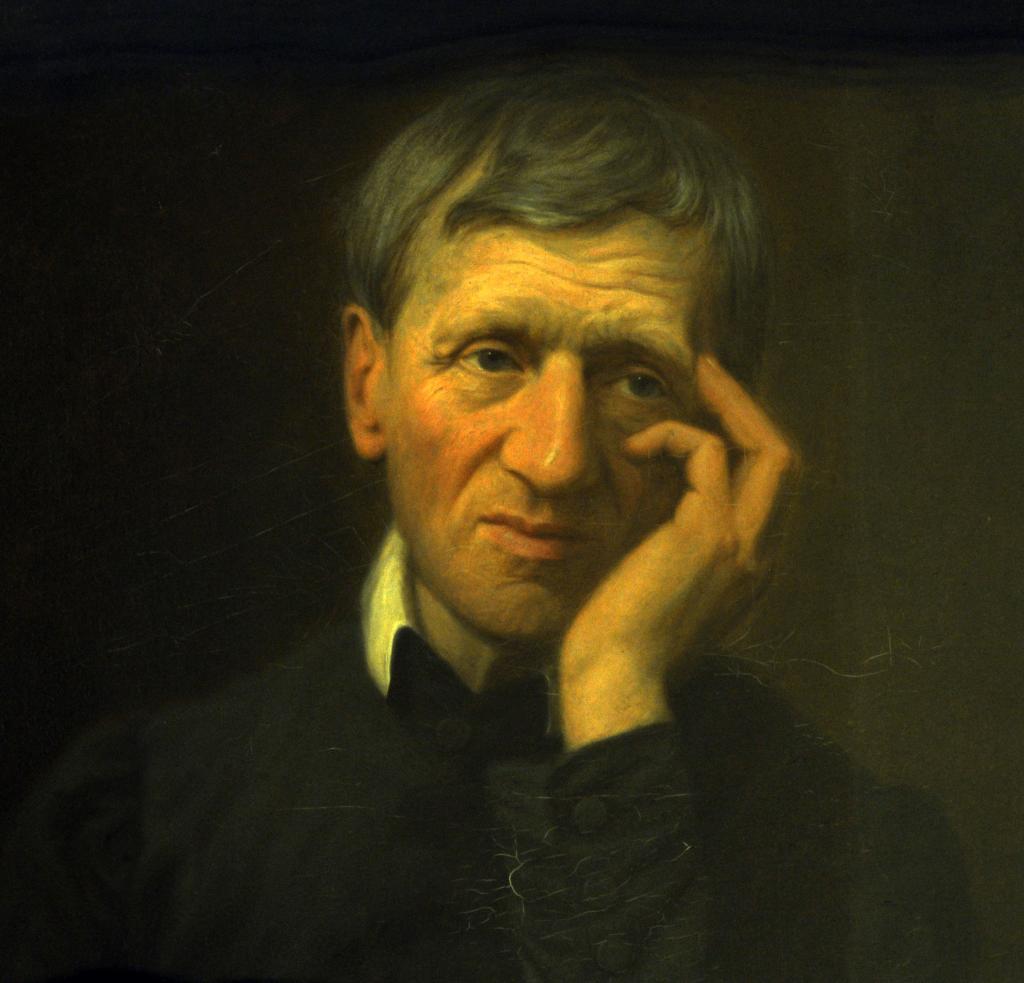

John Henry Newman, soon to be canonised, is meant to be a guide for us. Saints are models of Christian living. Yet he died peacefully in his bed in 1890, an old man and a Cardinal, honoured and respected.

How can he help us when we are in distress? We need to consider his story again.

Here was someone who had risen to great prominence. He was a priest of the established Church, the Church of England, and a fellow of Oriel College, at a time when that College was regarded as supreme among Oxford colleges. He was the Vicar of the University Church, a renowned preacher, and with his friends, Edward Pusey and John Keble, an influential leader of the Oxford Movement which was seeking to restore within the Anglican Church the Catholic tradition that had been allowed to falter. All seemed set fair for success. And what happened next?

To his surprise he was led by events and his own arguments to doubt the position in which he had felt so secure and, after careful study, in obedience to conscience, he left the Church of England to become a Catholic. It is difficult for us now to grasp the enormity of that act in the eyes of his contemporaries. He had abandoned a position of honour and prestige to join a small, despised minority. Many people regarded him with contempt. While some friendships endured, many cast him adrift. Even as dear and saintly a friend as John Keble made no contact with him for seventeen years. When he finally wrote to ask Newman’s pardon, his letter was moving. ‘I ought to have felt more than I did what a sore burthen you were bearing for conscience’s sake,’ Keble acknowledged. And Newman replied, ‘Never have I doubted for one moment your affection for me’ (Letters and Diaries 20, pp 501-03). Their friendship happily was resumed. But there had been many an anguished parting of ways.

And did the Catholic community which he had joined make up for what he had lost? Largely, no. Catholics in many ways were bewildered to have so distinguished a man in their midst. Some were suspicious and those in authority were unsure how to make best use of him. They would invite him to undertake projects, but then fail to put at his disposal the resources he needed for those projects to succeed. He was invited to found a Catholic University in Dublin, to oversee a new translation of the Bible, and to resolve a situation that had arisen over the distinguished, but controversial, Catholic periodical, The Rambler, by becoming its new editor. On each occasion, when it was needed, the necessary support was not provided. Other examples could be given. It was as though everything he turned his hand to ended in disaster.

His Journal entry in January 1863 makes sobering reading. ‘O how forlorn & dreary has been my course since I have been a Catholic!’ he wrote, ‘here has been the contrast – as a Protestant, I felt my religion dreary, but not my life – but, as a Catholic, my life dreary, not my religion.’ He was grateful for the blessings he had received, but the depressive tone is evident: ‘Few indeed successes has it been his blessed will to give me through life.’ And he concludes, ‘since I have been a Catholic, I seem to myself to have had nothing but failure personally’ (Autobiographical Writings, pp 254-5).

Soon afterwards, however, came the famous aside of Charles Kingsley, Anglican priest, Professor of Modern History at Cambridge, and novelist: ‘Truth, for its own sake, has never been a virtue with the Roman clergy. Father Newman informs us that it need not, and on the whole ought not to be’. This casual allegation that Newman was indifferent to truth gave him the opportunity he needed to explain himself. He knew it was what people had been thinking of him for many years, both as an Anglican and as a Catholic. In his Apologia pro Vita Sua he was able to set the record straight. And people’s perception of him began to change. Old friendships were renewed. All the same, his troubles didn’t end there. There were still further trials and controversies until in 1879 out of the blue, as it were, Pope Leo XIII decided to make him a Cardinal. And the final years were more tranquil.

The peaceful deathbed is misleading. Newman’s life had been beset by trials and sufferings and offers us a powerful illustration of someone who indeed embraced the paschal mystery, who modelled his life on the suffering, dying, and rising of Jesus, following faithfully the path of discipleship, wherever it might lead, at whatever cost. At the height of his fame in Oxford, he preached a sermon that contains a prophetic sentence that seems to reflect his own life quite remarkably. He declared: ‘The planting of Christ’s Cross in the heart is sharp and trying; but the stately tree rears itself aloft, and has fair branches and rich fruit, and is good to look upon’ (Parochial and Plain Sermons 4, p 262).

We too, like Newman, have to plant the tree of Christ’s cross in our own hearts, letting it put down deep roots. When we have done so, we discover that that stately tree does indeed grow tall and bears fruit and catches the eye. By embracing the paschal mystery, we bear witness to the way disaster may be turned into triumph.

Adapted from an earlier version with kind permission from Alive Publishing.