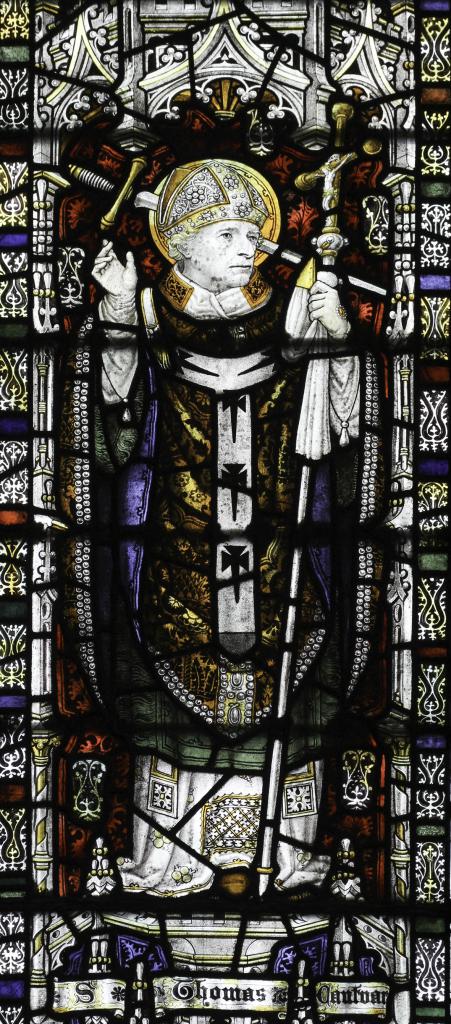

The Hungarian pilgrimage dedicated to St Thomas Becket takes place in May. The saint’s relics from the Diocese of Esztergom will be reunited with his relics from the Cathedral and become the focus of a week-long celebration. Ahead of the pilgrimage, Fr Nicholas Schofield explains the importance of St Thomas Becket for Roman Catholics in this country and, in particular, why we regard him as a saint.

The forthcoming visit of the relics from Esztergom is, indeed, a very exciting initiative and, along with the Church of England, we would hope it bears much fruit.

Compared to some popular saints, like St Francis or Mother Teresa, St Thomas is not perhaps an immediately attractive figure. He seems so closely bound to his age and as Lord Chancellor and then Archbishop of Canterbury, he was at times a rather difficult character. His behaviour often appears brash, arrogant and stubborn; he was criticised by his contemporaries just as much as by some modern historians.

But look a bit deeper into his life and a different picture emerges. Firstly, perhaps reassuringly for many, St Thomas is a very human figure and therefore surprisingly accessible. As Lord Chancellor, he enjoyed the wealth and power that his position gave him; as is portrayed in the film Becket, he and the King worked hard and played hard! But that all changed when he became Archbishop in 1162.

He seems to have experienced some sort of conversion. He saw his shortcomings and had the humility to change his ways, where necessary. In his own words, he went from being ‘a patron of play-actors and a follower of hounds, to being a shepherd of souls,’ spending much time in prayer and fasting, conscientious in his duties and generous to the poor. Indeed, for this reason, the Catholic Church today honours St Thomas as ‘Patron of the Pastoral Clergy of England’; he continues to be seen as a model for pastoral ministry and for parish priests.

St Thomas was careful to defend the Church from what he saw as ‘tyranny’. This was very much the spirit of the age, in which popes and bishops were eager, sometimes militantly so, to protect and promote their spiritual authority. Of course, in the twelfth century the spiritual and temporal powers were closely intertwined. It took many centuries for the relationship between Church and State to be worked out.

From a twenty-first century angle, it’s hard to feel the same passion as St Thomas over some of these emotive issues, such as the right of the Archbishop of Canterbury alone to crown a monarch or the much-disputed ‘benefit of clergy’ (i.e., Becket strongly held that clerics had the right to be tried by a church rather a secular court, though this did not necessarily mean leniency in punishment for the guilty). St Thomas saw compromise in these matters as the thin end of a dangerous wedge.

One of his modern biographers, Frank Barlow, claimed that his ‘truculence…not only protected the Church’s own rights but also helped to defend the rights of other men against tyrannical rulers.’ St Thomas saw himself as standing up to the pretentions of a regime that tried to compromise his freedoms. In this, I think, he inspires us today, even though we live in such different circumstances.

Christians honour St Thomas, of course, as ‘the holy blissful martyr’ (to use Chaucer’s phrase), a man who shed his blood for his beliefs and principles, who gave the ultimate witness to Christ. It was the nature of his death that shocked the world: an Archbishop struck down in his own Cathedral, while Vespers (or the evening service) was being sung, a few days after Christmas. Although the monks at Canterbury tried to prevent a cult from developing, it grew spontaneously among the sick and the poor, who claimed the murdered Archbishop’s miraculous intercession.

St Thomas was quickly canonised by Pope Alexander III in 1173; the following year King Henry made a penitential pilgrimage to the tomb of his one-time friend. Shortly afterwards, much of Canterbury Cathedral was destroyed by fire, allowing the monks to rebuild it as a magnificent shrine, not only the resting place of a saint but the location of his martyrdom.

St Thomas continued to take a central position in the national psyche long after his death, especially in the great pilgrimage made to Canterbury by rich and poor, the great procession of pilgrims including the likes of Louis VII of France (1179) and the Emperor Charles V (1520). This reminds us that St Thomas does not just belong to the English but left his footprint across Europe: from a church dedicated to him in Salamanca (opened just five years after his death) to an early fourteenth century Icelandic saga telling his story, from the mosaics depicting him in the cathedral of Monreale in Sicily (one of the earliest images of him to survive) to the medieval Hospice of St Thomas in Rome, founded for English pilgrims. The relics at Esztergom are part of this rich European tapestry, preventing us from being too ‘insular’ in our history!

It is also worth stressing that St Thomas is now very much a shared saint across the denominations: a figure of unity rather than division, allowing us to go beyond the turmoil of the sixteenth century, which resulted in the destruction of his shrine. There have been many positive developments in recent years and the pilgrimage to Canterbury is itself enjoying something of a revival.

I hope that the visit of the relic from Esztergom will help us celebrate all that we have in common and, at the widest level, promote our understanding of St Thomas. For me, this ‘holy blissful martyr’ continues to inspire with his willingness to change the direction of his life (when necessary), his fearless defence of freedom, his concern for pastoral work and the rich spiritual and cultural legacy that his life and death imprinted on England and, indeed, much of Europe.

Fr Nicholas Schofield is Parish Priest of Our Lady of Lourdes and St Michael, Uxbridge, and Archivist of the Diocese of Westminster.

The pilgrimage begins with the arrival of the Hungarian relics of St Thomas at Westminster Cathedral on 23 May.

Mass will be celebrated by Cardinal Vincent and Cardinal Peter Erdo, Archbishop of Esztergom-Budapest. Additional liturgies, talks and processions will take place, along with an opportunity to venerate the relics at different points of the pilgrimage. Further information about the pilgrimage will appear on the website in due course.

Photo: © Fr Lawrence Lew OP