by Fr Nicholas Schofield

Diocesan Archivist

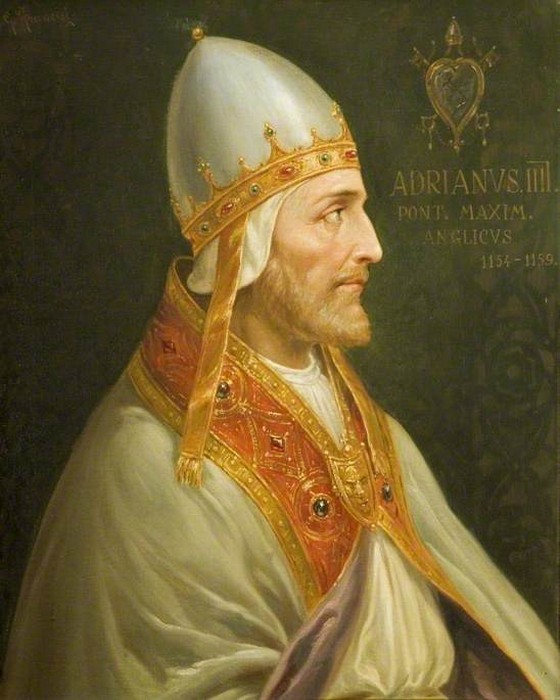

As I drive in the hearse to the local crematorium, a pub sign always intrigues me. It shows a man with a long white beard raising his hand in benediction. The pub is called the Breakspear Arms and the venerable cleric is one Nicholas Breakspear, or Adrian IV, the only English-born Pope, who died 860 years ago. The crematorium in Ruislip also bears his family name.

His birthplace is normally given as Breakspear Farm in Bedmond near Abbots Langley, Hertfordshire. However, a rival claimant is Harefield, although there is little more than local tradition to associate the future Pope with this corner of rural Middlesex, although members of his family certainly lived there in the late fourteenth century.

The future Pope was the son of Richard (or Robert), possibly a married priest who later became a monk at nearby St Albans. Tradition has it that young Nicholas also tried to join the Abbey but was turned away. In later life, as Pope, he is said to have pointedly refused the rich gifts of the Abbot of St Albans while accepting a homemade mitre and sandals from the Hertfordshire recluse, Christina of Markyate.

Breakspear may have studied at the newly-founded Augustinian Priory of Merton, Surrey, whose alumni also included St Thomas Becket, and went on to France, where he eventually joined the Augustinian Canons of St Ruf. By 1147 he had become their Abbot, although complaints were later sent to Rome about his strict reformist tendencies. The Pope removed him to keep the peace but it was clear that his talents had been noted. In 1149 Pope Eugenius III created him Cardinal Bishop of Albano.

If Breakspear had not become the first English Pope, it is likely that he would have been chiefly remembered for his energetic apostolate in Scandinavia, where he acted as Legate in the early 1150s. He facilitated the payment of Peter’s Pence by Sweden and Norway and created the bishopric of Nidaros (today’s Trondheim), a huge see embracing Norway, Iceland, Greenland, the Faroes, Shetland, the Orkneys and Sudreys (including the Isle of Man). He also reorganised the Swedish Church under the primacy of the Archbishop of Lund, thus ending its previous German dependence. The Cardinal is supposed to have written catechisms for the Swedes and Norwegians and a history of his Scandinavian mission, although none of these have survived.

Returning from Scandinavia, Breakspear soon found himself in conclave and he was elected as Pope Adrian IV on 4th December 1154. According to John of Salisbury, he found that the pallium was full of thorns and the mitre seared his head, preferring to remain a simple Canon of St Ruf. Little wonder because Rome was as challenging a place as Scandinavia: the city was in the control of a hostile commune, who killed one cardinal as he was on his way to visit the new Pope, and the Papal States were under attack from William I of Sicily. Adrian took immediate action, placing Rome under interdict and expelling and executing one of the commune leaders.

The Pope tried to win the support of the German Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, against the Roman mobs and the king of Sicily. But things started badly and got worse. When the two men first met at Nepi, Frederick refused to follow the custom of holding the Pope’s stirrup as he dismounted and Adrian declined to give the kiss of peace. However, the pope renewed a treaty with Frederick, which meant that both parties recognised the other’s sovereign rights, and crowned him as Emperor at St Peter’s in June 1155. The Emperor did not offer much support against the Pope’s enemies and was offended when Adrian made peace with William of Sicily, recognising him as King over much of southern Italy, with special rights over the Church in his domains.

Relations between Pope and Emperor grew increasingly strained. Adrian eventually fled to Anagni for safety and considered excommunicating the Emperor. He died at Anagni on 1st September 1159 before he could do so and was buried in an ancient red granite sarcophagus at St Peter’s. When his tomb was opened in 1607 he was found to be ‘an undersized man wearing slippers of Turkish make, and a ring with a large emerald’.

Adrian’s most famous (some might say infamous) involvement in English affairs was his bull, Laudabiliter (1155), supposedly granting Ireland to Henry II. Historians have argued over the document’s authenticity: the original document has not survived and we rely on Gerald of Wales, one of King Henry’s men, for the text. Even if Laudabiliter was the result of Angevin spin, it is clear that an English invasion of Ireland fitted in with the Pope’s aims of promoting ecclesiastical reform. The Irish Church, despite its key role in the evangelisation of northern Europe, was still largely ‘tribalised’ and based around the authority of powerful abbots (often hereditary) rather than diocesan bishops. Pope Adrian would have been keen to standardise its structure according to the Roman model. Henry eventually landed in Ireland in October 1171. English monarchs up until the Reformation based their title of ‘Lord of Ireland’ on the pope’s bull.

If some think Adrian was responsible for eight centuries of English domination in Ireland, we can be grateful for his strenuous efforts in the face of difficult circumstances as legate in Scandinavia and as the only English representative on the Fisherman’s Throne. And, best of all, he was a son of our diocese!