By Peter Stevens

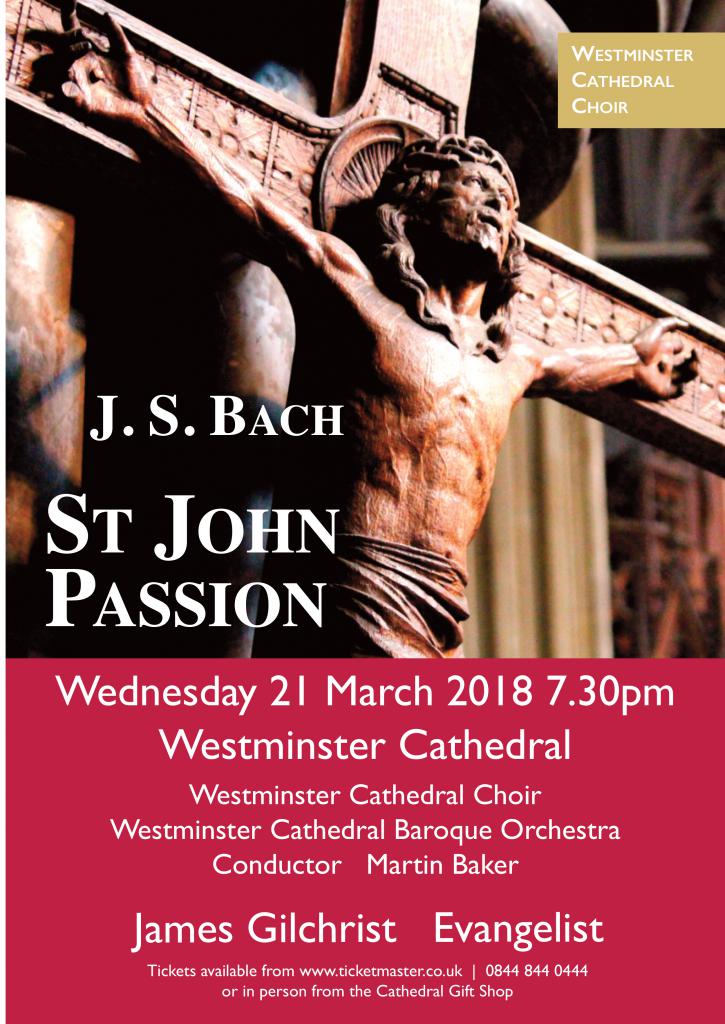

On Wednesday 21st March, Westminster Cathedral Choir and Baroque Orchestra, conducted by Martin Baker, will perform the St John Passion of Johann Sebastian Bach. One of the seminal works of the entire choral repertoire, and a milestone in the history of music.

By happy coincidence, Bach was born into a great musical family exactly 333 years earlier on 21st March 1685, in Eisenach, and lived his entire life in a small corner of present-day Germany. His work as Kantor (Director of Music) of St Thomas’s Church, Leipzig, involved the composition of liturgical cantatas for every Sunday of the Church’s year, and it was during his time in Leipzig that the St John Passion was composed. It received its first performance on Good Friday 1724, a year after his appointment, although a last-minute change of venue meant that the work was first heard in St Nicholas’s Church; Bach made a number of requests including the repair of the church’s harpsichord and the printing of a new booklet, and the authorities agreed to rectify the problems in time for the premiere.

However, whilst the work is heard around the world in concert, the St John Passion was originally intended for liturgical performance. The piece is divided into two parts, and in the original context of the Lutheran Good Friday liturgy, a sermon of considerable length, perhaps several hours, would have been delivered in between them. Bach takes as his text chapters 18 and 19 of the Gospel of St John, using the translation from the Luther Bible of 1534. Interestingly, two moments in Bach’s setting are actually drawn from the Gospel according to St Matthew: the weeping of St Peter after his denial, and the tearing of the veil of the Temple. Interspersed between the Gospel narrative, sung by the tenor Evangelist, a bass Christus, and a few other minor characters, are arias sung by soloists. These arias are settings of poetry that meditate on the action just heard in the story. As with the St Matthew Passion, written three years later, the work is structured around chorales: hymns, whose melodies and words would have been familiar to Bach’s contemporaries, and which put the story in a more familiar context.

The dramatic opening chorus, Herr unser Herrscher, provides a striking, vivid beginning to the Passion. After a brooding orchestral introduction, the choir makes its first appearance by declaiming three times the word ‘Herr’ (Lord), as a solemn hymn of praise unfolds in music of extraordinary gravity. Thereafter the chorus is used to play the part of the crowd, with sudden outbursts and more extended passages, notably the crowd calling for Christ to be crucified, where relentless rhythmic energy propels the music forward through intense, venomous harmony.

The story is narrated by the Evangelist in sections of recitative, where the text is sung in near-speech rhythms, accompanied by solo cello and organ. Bach’s recitative is full of subtle harmonic colour, passionate lyricism and moments of gripping drama. We are very fortunate that the tenor James Gilchrist, one of the most renowned Passion evangelists of our time, will be joining the Cathedral Choir for this performance. This will be the third time that he has joined us in the role of the evangelist: in 2013 he was evangelist for the St John Passion, and the following year he returned to sing the same role in the St Matthew Passion. This year, the part of Christus will be sung by the bass David Shipley, in his first performance at Westminster Cathedral. As well as being a notable soloist with many of the world’s great orchestras, he has made numerous appearances at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

The solo arias will be sung by members of the Cathedral Choir. Highlights include the passionate tenor aria, Ach, mein Sinn, depicting St Peter’s grief after his denial; Eilt, ihr angefochtnen Seelen, a bass aria which reflects on Christ being handed over for crucifixion; Es ist vollbracht for alto, as Christ hangs on the Cross; and Zerfließe, mein Herze, a meditation after the death of Christ.

As a mirror to the work’s opening, a substantial chorus forms the penultimate item in the St John Passion: Ruht wohl (Rest well) is an affecting lament as Christ is laid in the tomb. However, unlike Bach’s St Matthew Passion, the work does not end in darkness but with a note of optimism. The text of the final chorale looks forward to the vision of Christ’s glory, and to praising him forever.

Peter Stevens is Assistant Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral.