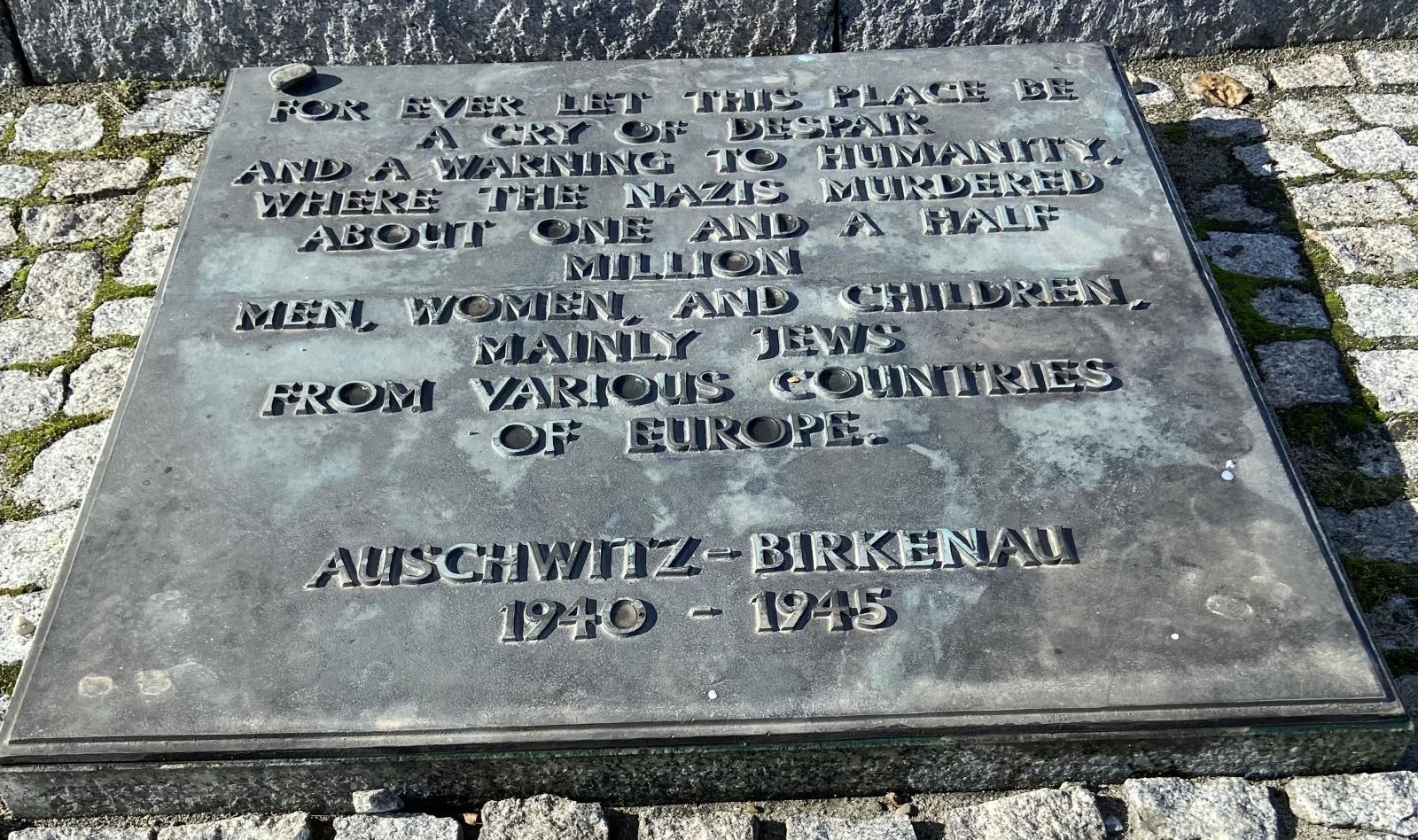

Holocaust Memorial Day is observed on 27th January, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp. It is a day for everyone to remember the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust, and the millions of people killed under Nazi persecution, and in the genocides which followed. This year, Bishop John Sherrington reflects on a pilgrimage to Poland organised by the Council of Christians and Jews.

Last October, a few days after the murder of 1269 Israelis by Hamas and the taking of hostages, and during those days when we awaited the response by Israel, I participated in a study week organised by the Council for Christians and Jews with a focus on the Holocaust. During the week, the participants, leaders of Christian Churches, were led by James Roberts and Nathan Eddy of CCJ with the assistance of Helise and Mosze of the Taube Centre for Jewish Life and Learning in Warsaw.

We visited Warsaw, Åódź, and Krakow, met members of Jewish communities and followed the paths of some of the six million Jewish people who died in the Holocaust. The experiences of that week provide a deeper understanding and greater poignancy as we approach Holocaust Memorial Day on 27 January.

Much of the preparatory reading for our study week focused on the narratives of survivors (e.g. Primo Levi) and historical research from both Jewish and Catholic perspectives.

Decisions in the face of evil ideology

We heard of the popularist rise of the Third Reich and rapid way in which discrimination against Jewish people developed, the marginalisation and herding of Jews into the Ghettos, the transportations East and the many ways in which Jews were murdered, whether in camps, shootings in the countryside, gassing in the backs of lorries, or by sheer starvation. This revealed the horror of the Shoah that resulted in the death of six million Jewish people.

I had always been interested in the question of moral complicity by non-Jewish people, for example, fellow neighbours and known shopkeepers, the train drivers, the signalmen who changed the points on the railway lines. The experience of the week in Poland highlighted more acutely the complexity of the situation and the free decisions that were made by some individuals as they confronted the evil of Nazi ideology and sought to be and do what is good and right.

Following the week of visiting sites associated with the Holocaust: the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw, walking the stones which marked out the Warsaw Ghetto, visiting the Umschlagplatz in Warsaw (the holding area from where Jews were transported to the camps), the Ringelblum Archive and finally Auschwitz-Birkenau, I looked for signs of hope that transcended the darkness of evil.

Following the week of visiting sites associated with the Holocaust: the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw, walking the stones which marked out the Warsaw Ghetto, visiting the Umschlagplatz in Warsaw (the holding area from where Jews were transported to the camps), the Ringelblum Archive and finally Auschwitz-Birkenau, I looked for signs of hope that transcended the darkness of evil.

Emmanuel Ringelblum organised the people of the Ghetto to record their daily lives as a chronicle of their fate for the future. It is hard to imagine the dedication with which letters were typed in Yiddish as conditions worsened and life deteriorated into starvation. Fortunately some of the letters were recovered after the war. Others were lost in the destruction of the Ghetto. Maybe some others will still be found.

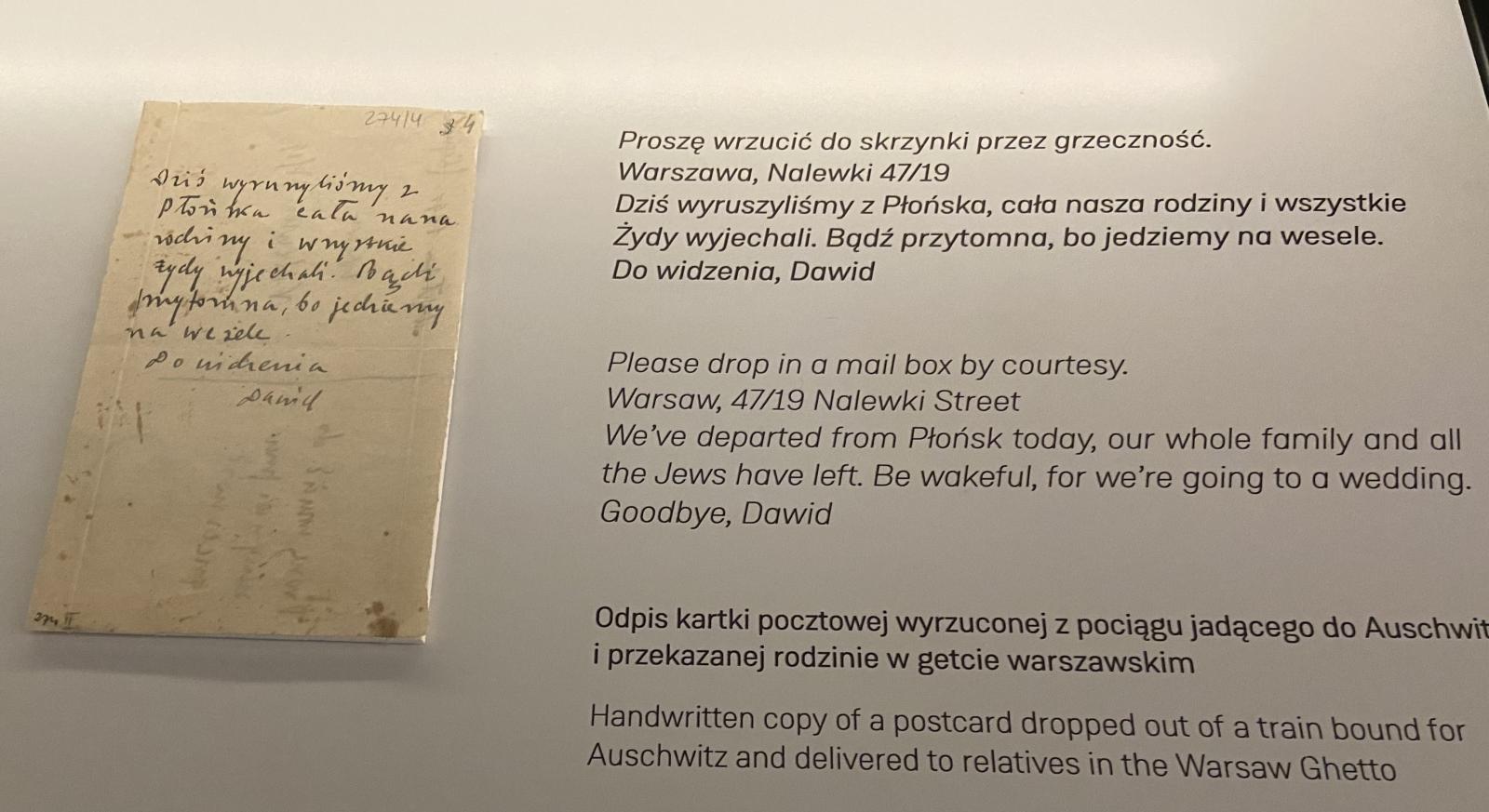

Poignant message

A small postcard in the Ringelblum Museum showed that, in doing little things in adversity, people can powerfully do good. The note written on a simple postcard was dropped from a train window en route to Auschwitz with a request that it be posted to a family living in the Ghetto. It read, ‘Please drop in a mailbox by courtesy. Warsaw, 47/49 Nalewski Street. We’ve departed from PÅ‚oÅ„sk today, our whole family and all the Jews have left. Be wakeful, for we’re going to a wedding. Goodbye, Dawid’.

The final words of Dawid were delivered to the family because someone bothered to pick it up, perhaps put a stamp on it, and post it. The Ghetto postman delivered it in accord with his duty. A tragic and poignant message that brought tears to my eyes but a sign of hope that people are good and are willing to help others.

The final words of Dawid were delivered to the family because someone bothered to pick it up, perhaps put a stamp on it, and post it. The Ghetto postman delivered it in accord with his duty. A tragic and poignant message that brought tears to my eyes but a sign of hope that people are good and are willing to help others.

Righteous Among the Nations

Another example of hope was found in the protection of Jewish people by Jan Zabinski and Antonina Zabinska at the Warsaw Zoo. As the director of the zoo, one of the largest in Europe before the war, but largely destroyed by bombing early in the war, Jan Zabinski was allowed to visit the Ghetto to tend the plants and small garden there. In this way, and through various means, he managed to smuggle Jews to protection in the zoo, hiding them in the cellars and underground rooms.

On September 21, 1965, Yad Vashem recognised Jan Zabinski and his wife, Antonina Zabinska, as Righteous Among the Nations. On October 30, 1968 Dr Zabinski planted a tree on the Mount of Remembrance. The record states, ‘Dr Zabinski, with exceptional modesty and without any self-interest, occupied himself with the fates of his prewar Jewish suppliers... different acquaintances as well as strangers,’ wrote Irena Meizel.

She added: ‘He helped them get over to Aryan side, provided them with indispensable personal documents, looked for accommodations, and when necessary hid them at his villa or on the zoo’s grounds.’

Regina Koenigstein described Zabinski's home as a modern ‘Noah's ark’. He and his wife, with the help of their son, hid Jewish people in the zoo and in their home while planning their path to safety elsewhere. Like many others, they are a sign of hope that does not judge people according to creed or race.

Bridges of prayer

In Åódź we met leaders from the Christian and Jewish communities and heard of work to remember together the Holocaust. We were to meet Cardinal RyÅ› who leads on Jewish-Christian relations but he was in Rome at the synod. Instead we met his Auxiliary Bishop Marek Marczak and a team of those involved in this work of reconciliation. Another sign of hope building bridges of prayer, encounter and dialogue.

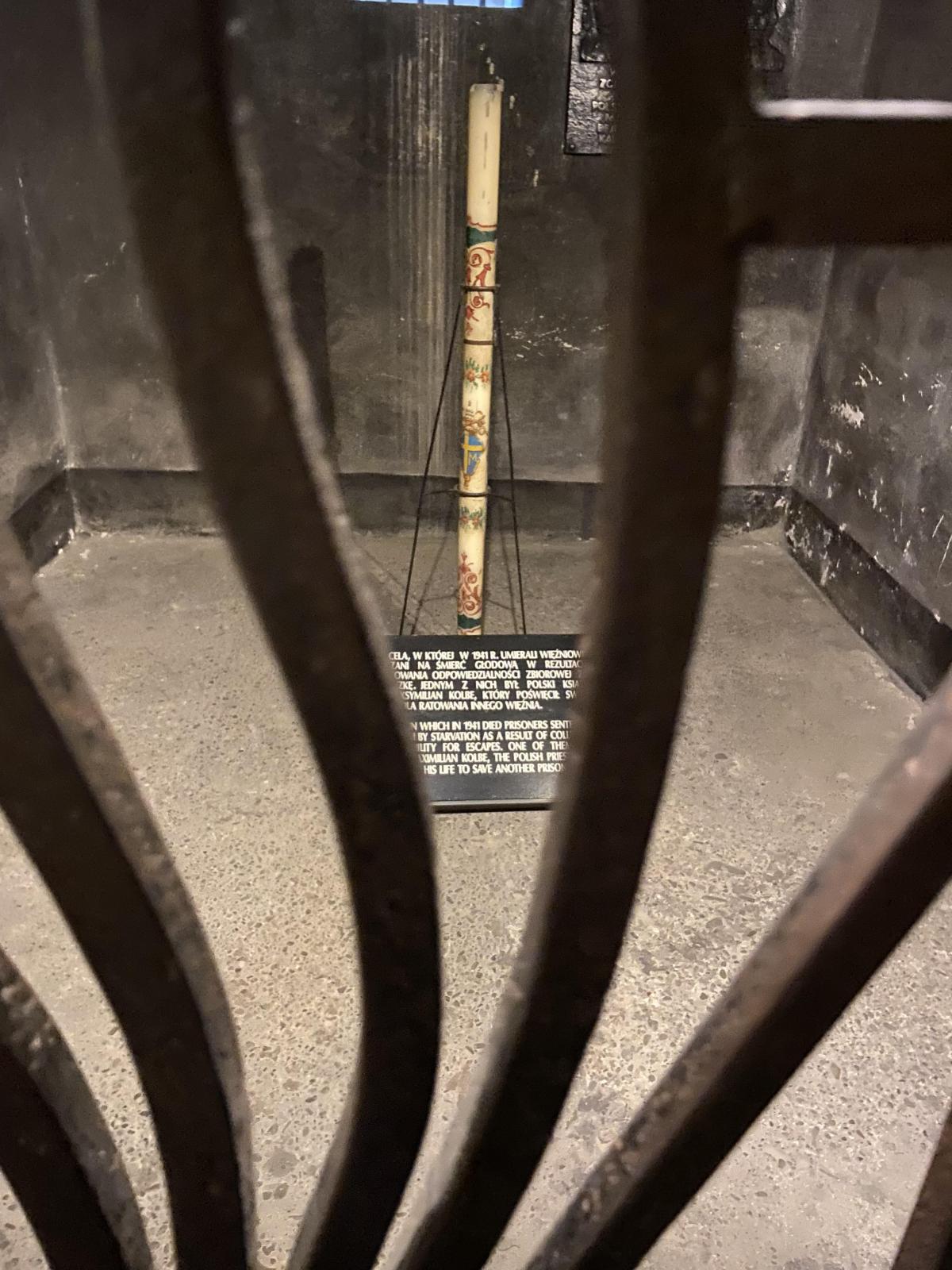

On the final day we visited Auschwitz. In the first prison camp, we visited the cell of St Maximilian Kolbe where he was imprisoned and ultimately murdered by lethal injection. The story is well known.

A candle burning brightly with hope

In July 1941, when three prisoners appeared to have escaped from the camp, the Deputy Commander of Auschwitz ordered 10 men to be chosen to be starved to death in an underground bunker. When one of the selected men Franciszek Gajowniczek heard he was selected, he cried out ‘My wife! My children!’

At this point, Kolbe volunteered to take his place. Gajowniczek later said: ‘I could only thank him with my eyes. I was stunned and could hardly grasp what was going on. The immensity of it: I, the condemned, am to live and someone else willingly and voluntarily offers his life for me – a stranger. Is this some dream?’

St Maximilian Kolbe survived the starvation and kept faith in prayer and hymn-singing. When all his fellow prisoners had died, he remained alive. As the Nazis wanted the cell for other men, they killed him by lethal injection.

As St John Paul said, ‘Maximilian did not die but gave his life … for his brother.’ He was cremated on 15th August 1941, the feast of the Assumption. In the darkness of that place, a candle in his cell can burn brightly with hope.

Remote possibility of hope

Another sign of hope is found in the writing of Primo Levi, quoted by Fr Timothy Radcliffe OP in the first meditation he gave at the recent Synod.

Each day Primo was given an extra piece of bread by his friend Lorenzo. He writes, 'I believe it was really due to Lorenzo that I am alive today; and not so much for his material aid as for his having constantly reminded me by his presence, by his natural and plain manner of being good, that there still exists a world outside our own, something and someone still pure and whole, not corrupt, not savage…something difficult to define, a remote possibility of good but for which it was worth surviving. Thanks to Lorenzo I managed not to forget that I myself was a man.'

The small fragment of bread preserved his humanity and saved his soul. The little steps of love give hope which breaks into the darkness.

Act of holiness

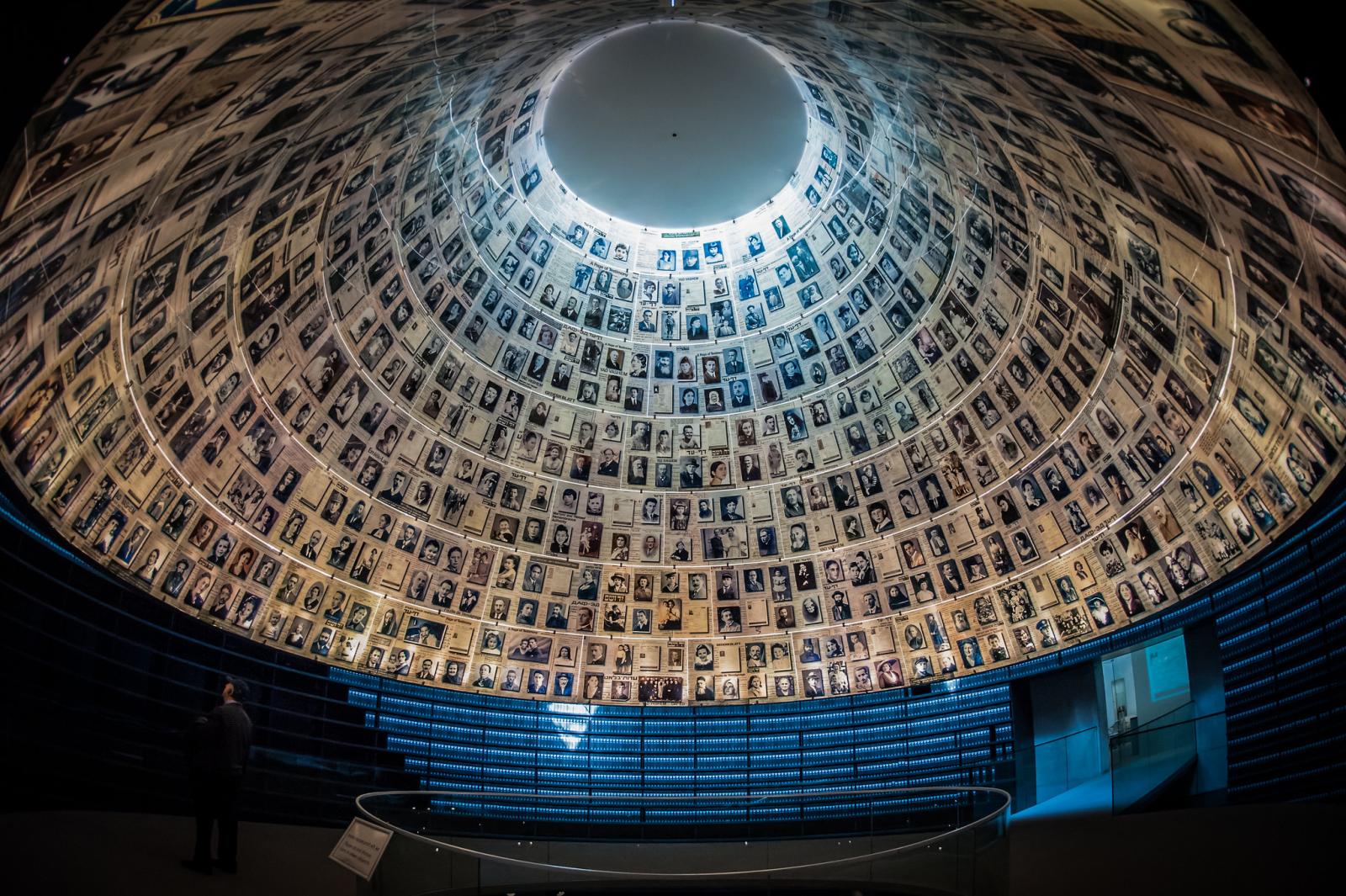

The final sign of hope was provided by Mosze from Warsaw who accompanied us on our journey. At Auschwitz, he showed us the list of the names of his family members who had died in the Holocaust. His finger followed down the list of names of a well-known Rabbinical family in much the same way as a Rabbi would follow the text of the Torah with a ‘yad’ or ‘hand’, the wooden or metal pointer for reading the Torah.

His movement and intonation was an act of holiness. That he could share his history and desire to build bridges between Christians and Jews is itself a sign of great hope. We met many others who like Mosze wanted to build bridges rather than put up barriers between peoples.

Gift of life

As I walked down the former railway tracks towards the infamous arch at Auschwitz, I noticed a few wildflowers that had tenaciously fought to bring new life into death. They stirred a deep feeling of freedom from within; I could leave, I was free, I was free to walk out and live. In contrast to so many who had never left, I was free with the gift of life. Life is the deepest hope we have; a life which finds its fulfilment in eternal life.

As I walked down the former railway tracks towards the infamous arch at Auschwitz, I noticed a few wildflowers that had tenaciously fought to bring new life into death. They stirred a deep feeling of freedom from within; I could leave, I was free, I was free to walk out and live. In contrast to so many who had never left, I was free with the gift of life. Life is the deepest hope we have; a life which finds its fulfilment in eternal life.

Over the week, I learnt again and again that, ‘man is redeemed by love’ (Benedict XVI, Spe Salvi 26). Such love is human and fragile, yet it is a fragile love that brings hope and is a precious gift.

Both Jews and Christians wait for the coming of the Messiah, whether for the first or the second time. This is our greatest hope: that the love of God is unending and eternal.

A Prayer For Holocaust Memorial Day 2024: The Fragility of Freedom

Eternal God, we come before you, conscious of the fragility of freedom, to remember the victims of the Holocaust.

We lament the loss of the six million Jews who were killed in the Holocaust, the millions of other victims of Nazi persecution, and victims of all genocides.

Remembering the past, help us today to use what freedom we have to stand up for those whose freedom is denied. We pray for a day when all shall be free to live in peace, unity and love. Amen.

Photos by Bishop John Sherrington and Mazur/CBCEW.org.uk